My bedroom looks like something from a miserable scene in Dostoevsky; cheap old furniture cramped into a small room, damp stains on the wooden floor, little cheery prints and posters of Polish churches , old brown icons and piles of blankets to shield against the cold. I have an excellent eye for antiques, and have a lot of porcelain I bought for next to nothing crammed into the room. I love Wedgewood and anything Art Nouveau I can stick a sickly palm plant in. No matter how much I clean, my bedroom never looks neat. I own more than enough stuff for my own house, but I am in a flatshare. Privacy is in short supply but that is something I am used to. My childhood bedroom, a slopping triangle with a skylight instead of a window had no door on the frame and I spent part of high school sleeping in a curtained storage room in a studio my parent was subletting, full of someone else’s things. I remember my first door, and I still love the sound of shutting one quietly.

I am not a compulsive buyer but have merely lived a life; a dress bought for a book launch of mine, books for research, a fold up Edwardian student desk from an old work place, old black Cameo cinema t shirts from my time working there and which they no longer use, a number of paintings from a recently deceased relative, train tickets from trips I remember with fondness, a teapot full of feathers my cat Ludwig gave me, water shoes for jumping in the abundance of sea in Scotland.

I am “what happens when people exceed the number of possession that their circumstances and standing would ordinarily allow.” As Olivia Laing says in The Lonely City, in a chapter about Henry Darger and Vivien Maier, two working class artists with limited access to space. Unlike Darger or Maier, I am fortunate to have my creative work recognized in my lifetime, though it doesn’t give me enough income to live off, it’s a comfort in dark moments to know I am for the most part, not invisible for now.

I love big old houses immensely and a couple of weekends ago I went to visit Newhailes House, a Palladian pile in Musselburgh, a seaside suburb on the edge of Edinburgh. It has a large park surrounding it where people in quilted Barbour coats walk their vizslas and cry shrilly after wayward toddlers with whimsical names.

Newhailes was started in the 17th century, and two large, symmetrical sides were added to the original house. It had been predominantly owned by a family called the Dalrymple’s (which sounds like the surname a well-meaning but careless Dickens character) was handed over to the National Trust of Scotland in 1997, after its last owner Lady Antonia died and nothing much has been changed since, only restored, maintained, old silk walls and 18thcentury dresses put in proper storage until there is funds to display. Samuel Johnson and James Boswell visited the house after their highland adventures, exclaiming it was “the most learned drawing room in Europe”. It was fun to imagine Johnson, like a rotting turnip in a big overcoat, standing in the dark wood and shuttered library(the books now gone to the national library of Scotland) where you felt you were submerged in Bovril and the aftertaste of smokey, mid-century parties lingered.

In one of the parlours there was a shelf of Chinese plates, all with chips in them as if each one had been dropped. Our guide told us they never threw anything away. I have a plastic bag of chipped crockery under my bed including a beautiful old pot I fancy making mosaics out of someday.

I felt an affinity with Lady Antonia: the multiple cat doors for her feline friends, Huxley novels and Lorna Doone, the tiny room full of her dead husbands old clothes. I have a collection of single socks from ex-boyfriends, long and purple, thick wool and red. I ought to make them into cursed dolls. Like me, she had a sibling who suffered from severe mental illness, unlike mine, hers was in the House of Lords after having a lobotomy. The different between us was space and money. Nathalie Olah, in Bad Taste says “hoarding is almost never considered a dysfunction in the wealthy with their sprawling homes- the notion almost ceases to exist once you enter that world.”

Such houses also inevitably have staff. The owners don’t have endless hours eaten up by washing dishes, scrubbing bathtubs and wandering through grocery store aisles, looking for the cheapest coffee. Newhailes as a building hid the presence of staff. There were dumb waiters and clever folding, origami like walls including one which created a temporary hallway between a wash closet and an exit from a bedroom so that whoever was sleeping there didn’t have to see a maid take away their chamberpot in the morning. I have always wondered if, in the age of chamberpots, servants had to train themselves to not make expressions when carrying such a parcel, and did they gossip about it to other staff, as I would, indeed as I have, cleaning bathrooms in customer service. There was a tunnel, running from the house to the barnyards and gardens so servants wouldn’t be seen running across the front yard. We got to go in, and it was dark and I envisioned some poor girl, trying to walk quickly down it holding a basket of eggs.

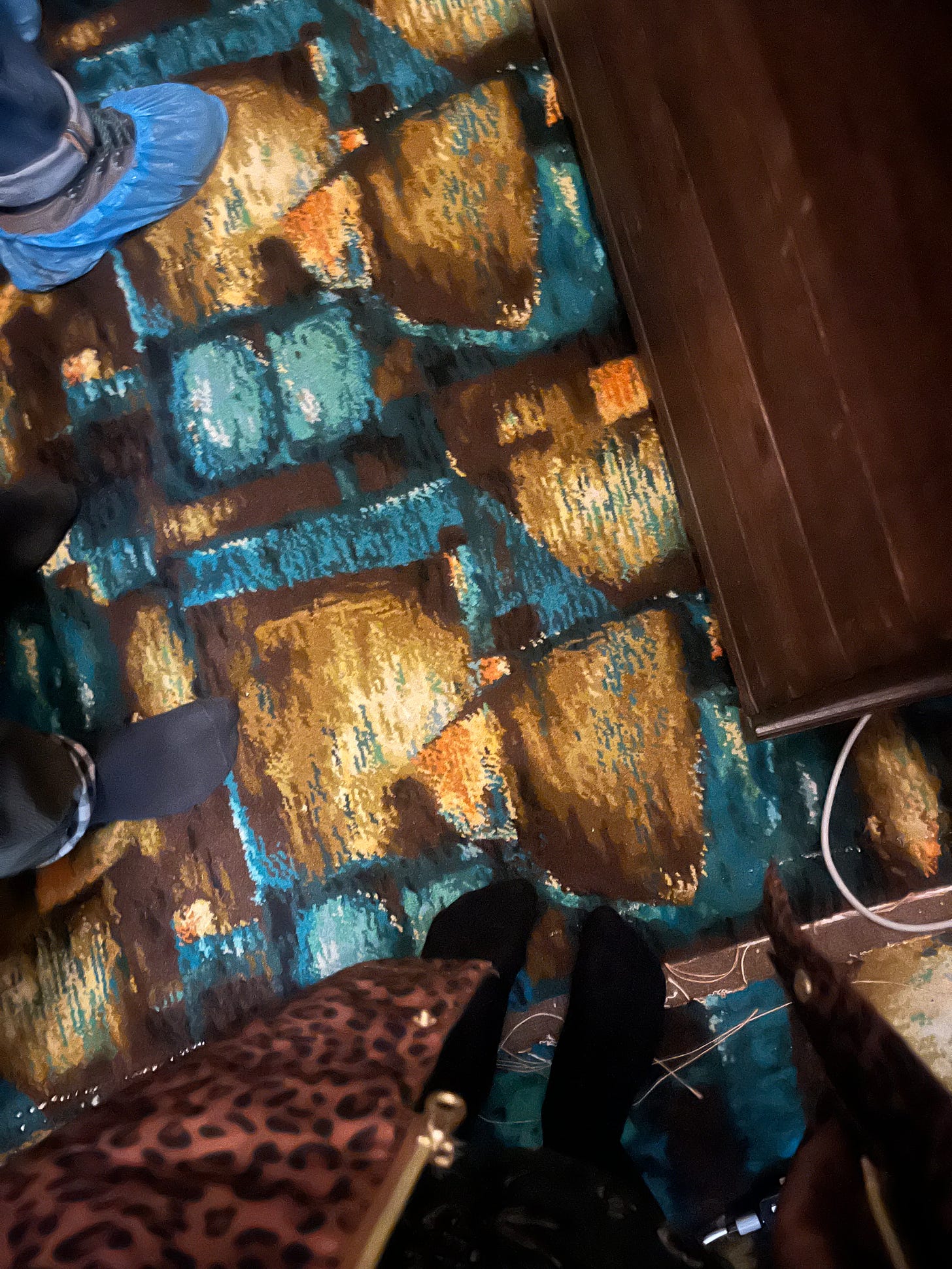

Most of the house was an aesthetic jumble of the 17th, 18th and 19th century but our guide took us around, our curiosity was piqued by a funky turquoise shag carpet in a small bedroom, which fortunately was part of the tour. The rest of the room was still Victorian, original William Morris Wallpaper, toad green and read, a muddy landscape built into the wall above the fireplace, a Jane Eyre worthy bed. Why the 70s carpet, like something furnishing a teenage rec room? The guide told us it had been a maid’s room and she had asked the owners if she could change the old décor- they said no, and while I am grateful to have seen original William Morris wallpaper I don’t think I would have wanted to sleep in that room either, like being trapped in an a decaying chocolate box. They told her she could change the carpet only and indeed she did, choosing something wonderfully garish. She made herself seen, and left her mark.

The flat share I am in now was unfurnished when we signed a lease, unlike most rented accommodation in the UK, and I enjoyed searching through charity shops for cheap, interesting things. In my previous, furnished flat, I had made the costly and irrational decision to disassemble a whiteboard wardrobe I loathed. I was resentful that someone else had decided what I needed and what it should look like, that I was one of many temporary residents, and should therefore keep my personality and possessions to a minimum. Nathalie Olah says of this in Bad Taste “To rent was to be prevented from decorating and to keep one’s living space as unencumbered as possible for the sake of attracting the next round of tenants.”

I have always liked objects, whether interesting looking sticks, China boxes or figurines, dollhouse furniture or teddy bears, they are full of stories and symbolism, a residue of life which can die or disappear so suddenly and it’s my circumstances, not my mental state which render that a problem. In spirit, I am an old country house and it comes across in my fiction which tends to contain a lot of lists and things . In The Elizabethan Lumber Room, Virginia Woolf describes the work of the 16th century author Richard Hakluyt as a “lumber room strewn with ancient sacks, obsolete nautical instruments, huge bales of wool, and little bags of rubies and emeralds. One is for ever untying this packet here, sampling that heap over there, wiping the dust off some vast map of the world and sitting down in semi-darkness to snuff the strange smells” I have a need, in my fiction, to create such lumber rooms. Woolf’s ‘Room of One’s Own’ isn’t available to me, I don’t have a private income. Instead I have a “One Room for Everything I Own”.

Completely identify with the old house metaphor and love of things. Missing you on Instagram!