time time time

I started the year two weeks late, celebrating New Years on the 14th by the Julian calendar while ignoring the bombastic and commercial Hogmanay. On the 15th, I was cheery, listening to the Irony of Fate soundtrack, but with the extra time I still managed to fuck this year up, having taken too long and too late to realise arts grants are taxable, so I am starting off the year with a pickle bigger than the ones I ate with vodka on the 14th. Another year and I still don’t know how to function like an adult, life is a coat I have only half put on. Irony of Fate, anyway is worth watching if you haven’t. One telling of communism, it is telling of capitalism too.* You can visit any city and eat the same meal and sleep in the same hotel and date someone with the same bmi and surgical enhancements. Travel addicts and explorers have become criminally boring. The most interesting people I know have barely or never left the UK.

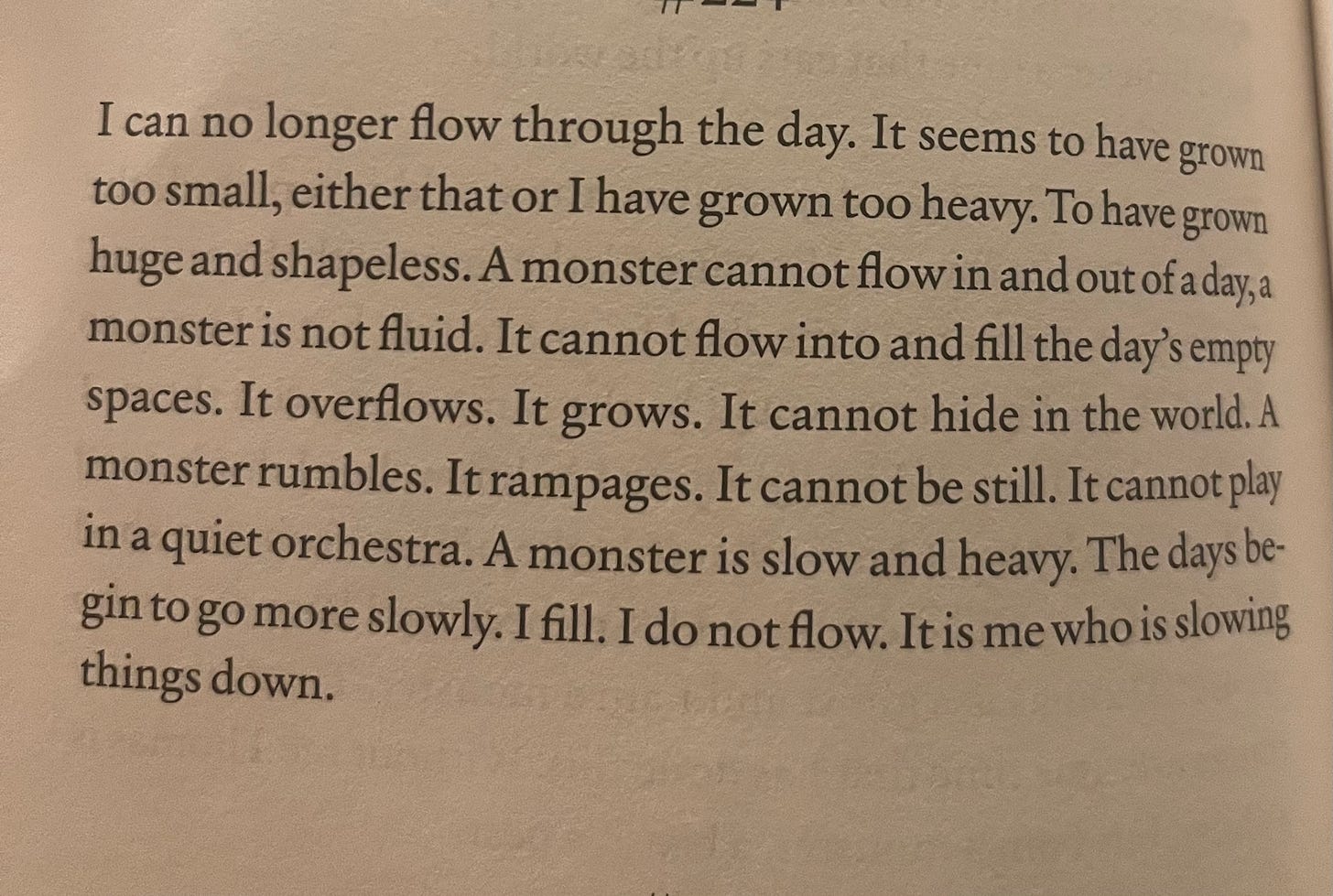

Last night I finished the second volume of The Calculation of Volume by Solvej Balle which rewired how I think of space and time. I think the last time pretty much everyone I knew was reading the same book was The Neapolitan Quartet. I am a bit daunted to read the third volume because there is a dramatic change, and the first two are so eloquently about loneliness and depression but I will and probably will read it compulsively in a day. The series is about Tara, an antiquarian bookseller stuck on the 18th of November, and it works so well because of the uncanny relationship she has to objects and food. They disappear unless she sleeps close to them ( at one point she puts a half eaten roasted turkey in an ice bag at the bottom of her bed)but if she goes to the same cafe every morning and orders the same thing, it eventually disappears from being for sale. She is still eating away at the world like every other human and leaving a trace, the day she is trapped in slowly diminished.

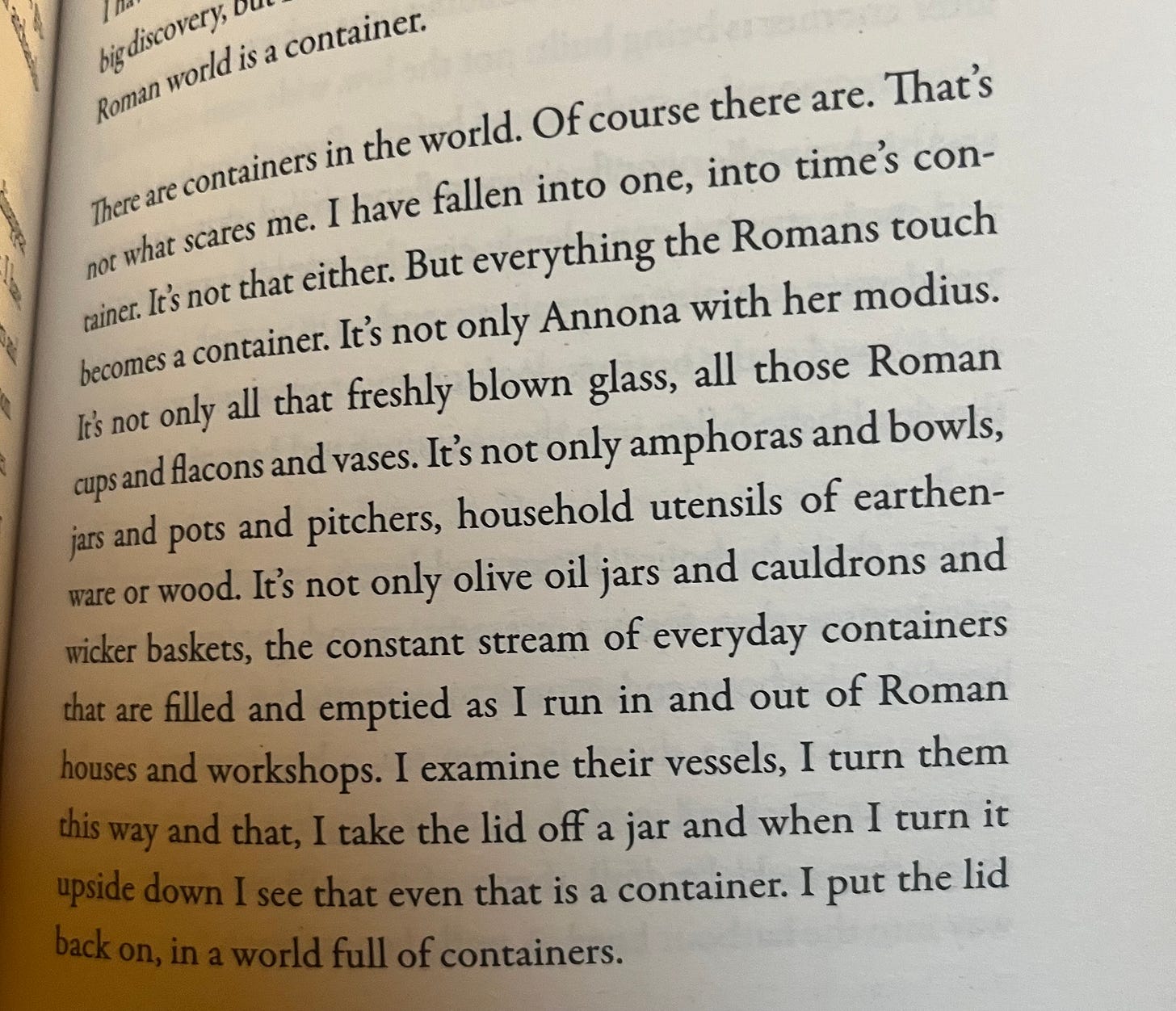

In the second volume the idea of a ‘container’ is central, it is filled with pre-boxed salads, bags, memory sticks, and the narrator falls into an obsession with the Roman Empire which she interprets through the idea of a container:

I think she finds comfort knowing the Roman Empire will shatter and that the one she is trapped in will too. The dissipation of the Roman Empire is almost a comfort for us as well, it lets us see an inevitable path out of the American empire loop and hegemony.

( I saw the film Sentimental Value recently and it contains an argument against having an ‘American’ version of the film made with famous Hollywood actors which is annoyingly done with many European films. The film is standing up for itself, and for the culture of small countries. It also does successfully what Hamnet tries to do, chart the possible catharsis potential of art, but then the Beckham saga is way more Shakespearean than the Hamnet film or book. It’s like Hamlet, Macbeth and the Henriads rolled into one. It’s terribly tempting to make memes of the Beckhams with Shakespeare quotes. ‘And I beseech you instantly to visit/My too much changed son.’ )

Tara desperately travels around, chasing the seasons in a way that will make you mediate uncomfortably on climate change in a way soppy agitprop novels on the topic won’t and also the arbitrariness of travelling. The series were first self-published by Solvej Balle, which says a lot about the publishing industry (They probably would have first marketed it as a ‘retelling of Groundhog Day from a Feminist perspective” and made her add more action) and she started writing them pretty much around the time I was born.

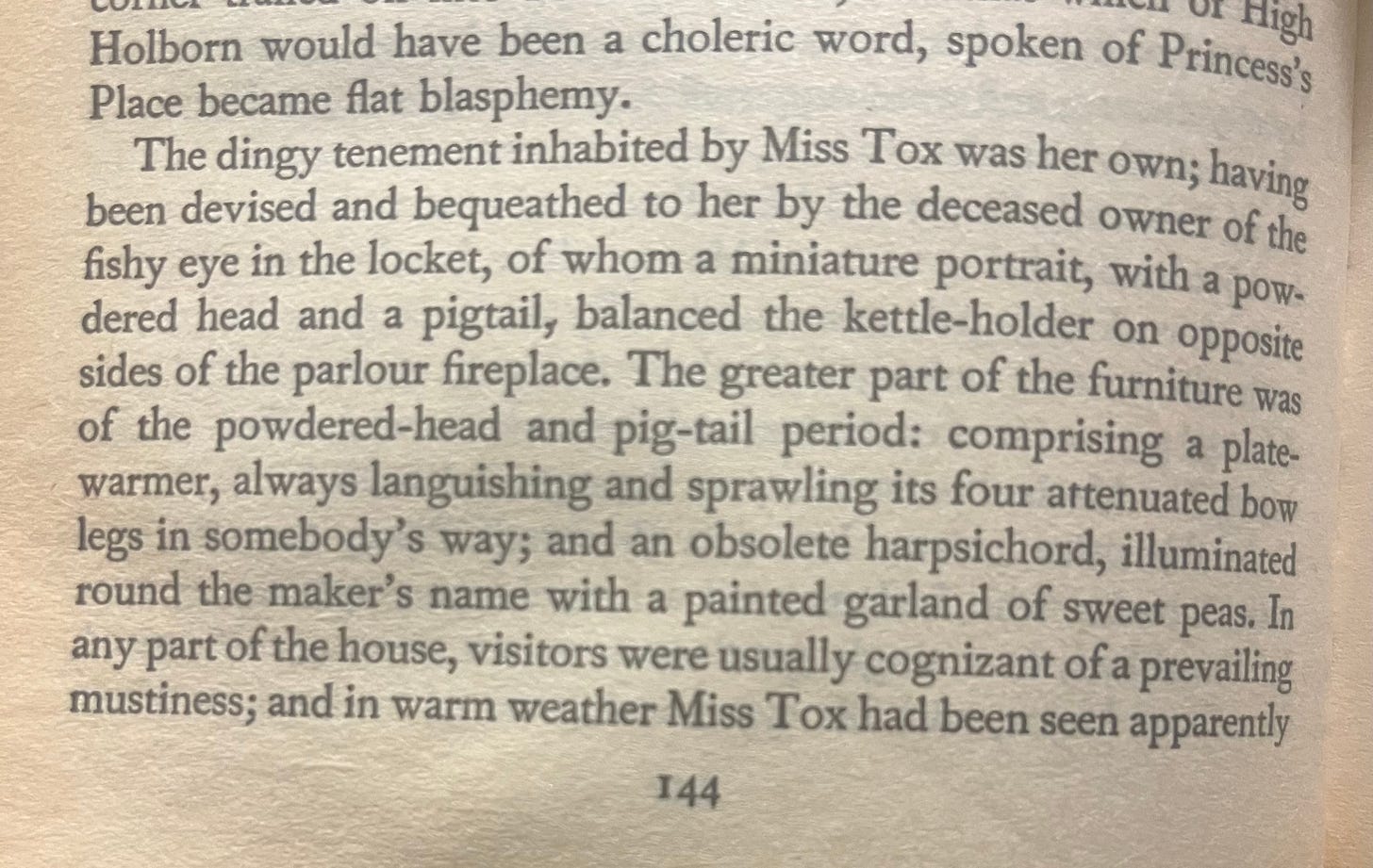

In Dombey and Son I found a perfect paragraph and why I love Dickens so much:

especially that line ‘an obsolete harpsichord, illuminated round the maker’s name with a painted garland of sweet peas,’ an illusory fresh green flora in a musty room. AI writing is painfully abstract, emotional and disembodied and I reckon we will more and more take comfort in cluttered 19th century novels or the domestic details of Life: A User’s Manuel. Perhaps why Perfection has been such a hit though I find its contemporariness not compelling . This paragraph also captures the problem I have with a lot of historical fiction, that it can exist in a vacuum sealed idea of a particular time without any evidence of the past huddling behind and prodding the decade or year we have chosen. We think of say, 1847, when Dombey and Son was published, as ‘the past’ and don’t see that there was a past before that. The 18th century is a smelly old ‘powdered-head’, slightly disdained presence in 19th century novels, its existence had not simply disappeared into thin air, replaced entirely by 19th century objects ( as it is in some contemporary historical novels set in the 19th century.) The harpsichord is viewed by Dickens the way we might view a 1960s hammond organ or a bulky grey computer monitor. I like paying attention to how older people are dressed in novels from the past too, that an old woman in the late 1960s will still dress in the fashion of the 40s.

I keep trying to write historical fiction and failing, I think the desire comes from a contemptuous dislike of the now, but I always end up settling on a non time, which I guess is, without my choosing, kind of a now time by default. I don’t like a self consciously contemporary novel, a manic desire to capture things just as they are as if the internet will disappear and that novel will be used as future proof of its existence as well as that of oat milk.( not super fascinating, there were soy sausages and soy milk in Stalinist Russia.) The Calculation of Volume captures the feeling of the last 30 odd years, of being trapped under a big plastic container, of wormholes and endless consumption, and also renders it uncanny because it doesn’t shy away from the metaphorically speculative.

*footnote edit. I think you could reasonably argue we are living in a hyper Soviet world!

I very much agree about historical fiction— a related thing I find frustrating is when the fact we know what happens next hangs too much over the period itself.

I think that sometimes gives us in the setting’s future a sort of assurance I’m not sure we’ve really earned: seeing events in our own past as inevitable, when we don’t really know if they are.

But it also forces tragedy on people who have no idea their lives will become tragic; happy endings on people who are sure their futures are bleak. It’s a bit dehumanising to steal the unknowability of the future from people in your knowing way, I always think. Obviously the people are fictional in this case; I still get affronted on their behalf.

I really want someone to write a novel in 1816 or so with this in mind; it always sounds like a truly bleak moment to live through, but it’s not really seen that way when we have the ability to look back on it. “Winter came in summer and there wasn’t any food left!” I say, and people go “oh, because of the volcano.”

But they didn’t know that then. They didn’t know their hope for Queen Charlotte would never materialise, but the age that was coming would be named after a woman who was conceived as a result of Charlotte’s death. The Victorian era swamps their era, but even the word “Victorian” would have been baffling then. I’m rambling now

One of my favourite Dickens paragraphs is this one from David Copperfield, for some reason: